Food and Drink: Regional Cuisine

German food inevitably conjures images of beer and pretzels, sausage and dumplings, probably enjoyed in an Oktoberfest-style Biergarten. True, these stereotypical foods are an integral part of German life and culture, but mostly in Bavaria, one of the 16 federal states of Germany. That leaves another 15 states, each with countless subregions and local culinary traditions. This culinary diversity has to do with Germany’s fragmented political history—before unification in 1871, it was a loose association of hundreds of kingdoms, each with their own linguistic, cultural, and culinary particularities.

Germany sits at the geographical heart of Europe, and its regional cuisines are influenced by its neighbors: France and Switzerland to the southwest, Poland and the Czech Republic to the east, Austria to the south, and the Netherlands and Scandinavia to the north. In the relatively cold climate, staple crops like potatoes, cabbage, and onions thrive, which is reflected in the nation’s hearty fare. Germany’s cuisine is also heavy, with an emphasis on pork and sausage (there are some 1500 officially recognized varieties of Wurst alone), as well as cheese and dairy products. Germany is known the world over for its beer as well as its Riesling white wine.

Regional recipes are often a variation on a dish eaten nationwide: a Sunday roast in the southwestern state of Baden-Württemberg, for instance, might be served with egg noodles called spätzle, while potato dumplings would accompany the same meal in Rhineland-Palatinate.

Beyond traditional rustic fare, there is also an emerging culture of haute or new German cuisine with an emphasis on farm-to-table ingredients and refined presentation methods. In fact, Germany has the most Michelin-starred restaurants in the world after France. But the heart of German cuisine remains deeply rooted in traditional recipes showcasing seasonal ingredients and handcrafted meats and cheeses.

Baden-Württemberg

While more than a quarter of all the Michelin-starred restaurants in Germany are located in Baden-Württemberg, the local haute cuisine exists alongside a rich tradition of farmhouse and artisanal cooking. Located in the southwest, Baden-Württemberg borders Switzerland and France, and like its neighboring cuisines, is heavy on wine, cured meats, and cheese and dairy products. With the warmest climate in Germany, this region is also particularly suited for high-quality wine, fruit, and vegetable production.

The culinary tradition of Baden-Württemberg can further be divided into Baden and Swabian cuisines. The former is the sophisticated, French-influenced cuisine of the spa city of Baden-Baden, while Swabia boasts a simpler, more down-to-earth style of cooking with an emphasis on rustic dishes such as egg-noodle stews.

Schwarzwälder Kirschtorte. Black forest cake is a decadent chocolate cake filled with cream and cherries, drenched in sweet Kirchwasser (cherry schnapps), topped with fresh cherries, chocolate shavings, and more cream.

Schwarzwälder Schinken. Black forest ham is cured in spices such as garlic, coriander, pepper, and juniper berry, cold smoked, and then air dried—a process that can take up to three months. But the result is clearly worth it as Black Forest Ham is the best-selling smoked ham in Europe.

Maultaschen. This German-style ravioli is filled with meat or cheese and vegetables. In the local dialect, they are called Herrgottsbscheißerle, meaning “little God cheaters,” in reference to the monks that used to eat them during Lent to hide the meat they were eating from prying eyes.

Gaisburger Marsch. This substantial beef stew brings together the two staples of this regional cuisine—fresh egg noodles and potatoes—into one carb-heavy dish.

Dampfnudeln. This sweet, white bread roll is cooked, as the name implies, with steam in a closed-top pot. As a main, it is served with cabbage and meat or as an accompaniment to soup while as a dessert, it is typically served with custard or fruit.

Bavaria

When the rest of the world thinks of German cuisine, it’s probably Bavarian food and dining culture that first come to mind: overflowing steins of beer and wooden platters heaped with dumplings and sausage. The region has a long tradition of beer brewing and is home to the world-famous Oktoberfest. The famous 15th-century German Beer Purity Law, Reinheitsgebot, stipulates how beer can be produced and was promulgated in Bavaria.

Although Bavaria is now rich and tech-heavy, it was decidedly rural for most of its history with a strong tradition of hearty, earthy foods. Cabbage, beets, and onions are the bedrock, and potatoes or bread are served at virtually every meal. Perhaps more so than other regional German cuisines, Bavarian cooking has a tendency to use all parts of the animal, and in the past decades, such dishes have begun to be seen less as poverty food than as a point of pride—a marker of the resourcefulness of the Bavarian identity.

Bavaria has also given German cuisine the concept of Brotzeit, a savory snack of bread or pretzels with toppings such as salted radish, egg, mustard, or butter eaten between breakfast and lunch.

Spätzle. A mainstay of southern German cooking, Bavarian spätzle are tiny fresh noodles made of egg and flour, cooked quickly in boiling water and served immediately, often as an accompaniment to meat or game dishes. The name translates to “little sparrows," and the jury is still out on whether they are actually noodles or dumplings.

Weisswurst. "White sausage" is a traditional Bavarian parboiled sausage link made of veal and pork that is characterized by a very smooth texture. Because traditionally no preservatives are added, they used to go bad quickly before refrigeration was widely available; for that reason, Weisswurst is still generally eaten only for breakfast or brunch.

Schweinshaxen. Pig’s knuckle is a beloved Bavarian recipe in which the meat is slow cooked to tender perfection in a brown beer sauce.

Lebkuchen. Christmas in Germany just wouldn’t be the same without Lebkuchen, a type of soft, spongy gingerbread typically glazed with sugar or chocolate. The dough is incredibly fragrant due to the sheer number of spices used: liberal amounts of aniseed, coriander, cloves, ginger, cardamom, and allspice are traditionally added. A mainstay of Christmas markets, Lebkuchen come in different shapes and are often inscribed with sentimental messages.

Rhineland-Palatinate

The federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate, located in the southwest, was historically one of the poorest regions of Germany; many of the Germans who immigrated to the United States during the 19th century came from this state. While the temperate zones of the Rhein and Mosel river basins are particularly conducive to growing fruits and wine grapes, especially Riesling, the interior of the state is more challenging to farm due to the rocky soil and mountainous terrain. Only very hearty plants like potatoes, onions, and beets can thrive here. The cuisine of Rhineland-Palatinate reflects these different climatic and geographical zones in the emphasis on hearty meat and potato dishes, complemented by wines and fruit desserts.

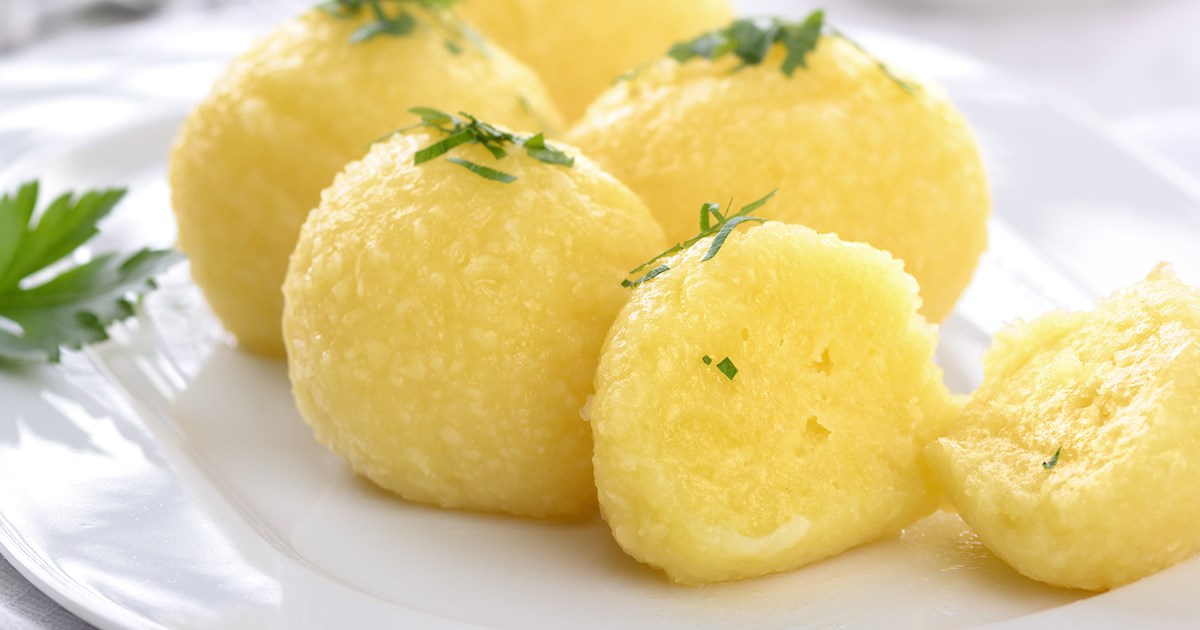

Gefüllte Klöße. This giant potato dumpling is stuffed with ground meat and leeks and dressed in a rich bacon cream sauce. Served with a side of applesauce, this dish is the ultimate comfort food, Rhineland-Palatinate style.

Sauerbraten. This sour pot roast is considered one of the national dishes of Germany, with the recipe from Rhineland-Palatinate being one of the most popular regional variations on the theme. The meat (usually beef) is marinated for several days in red wine and/or red wine vinegar and sugar to tenderize it and to allow it to absorb the characteristic sour-sweet flavor. Potato dumplings and red cabbage are typical accompaniments.

Saumagen. Saumagen, or “sow’s stomach,” is similar to sausage, except stomach is much thicker and wider than the intestines that are used for sausages. The stomach is stuffed with pork, potatoes, carrots, and spices such as onion, marjoram, and white pepper. The recipe stems from the days when poor farmers would scrape together leftover ingredients to make something resembling a roast.

Zwiebelkuchen. This is a quiche-style cake of steamed onions, bacon, cream, and caraway seed atop yeast dough. It is traditionally eaten in the autumn with a glass of Federweisser, a carbonated alcoholic beverage made from freshly pressed grape juice.

Thuringia

Located in east-central Germany, the Free State of Thuringia is considered the green heart of Germany due to its heavily forested landscape and rural character. With more than half of the state’s land devoted to agriculture, Thuringia is noted for its production of wheat, beets, onions, cauliflower, cabbage, and potatoes—popular ingredients in the local cuisine.

Thuringia was one of the areas of Germany to industrialize rapidly in the 19th century, and factories were built next to the farms where the food was produced, giving Thuringia a strong tradition of food processing and meat packing. But food production in this region is even more deep-seated: a Thuringian law stipulating the rules for manufacturing local Rostbratwurst dates to 1432, making it the oldest purity law for food production in Germany.

Thüringer Bratwurst (Thuringian Sausage). Thuringia is famed for its grilled bratwurst, a long, rather thin white pork or veal sausage. It’s so beloved, in fact, that the average Thuringian consumes upwards of 60 Rostbratwürste per year! This particular variety of wurst is distinguished by its low-fat content and savory spices, including marjoram and caraway.

Thüringer Klöße. Potato dumplings are consumed throughout Germany, but Thuringia’s potato dumplings stand out for their exceptional consistency, arising from the ratio of two parts hand-shredded potatoes mixed with one part cooked mashed potatoes. They are then shaped into a ball stuffed with roasted croutons.

Stolzer Heinrich. A combination of local Thuringian sausage with a spiced beer sauce, “Proud Henry” does the region proud.

Saxony

Saxony has a long and tumultuous political history as it has been part of the Holy Roman Empire, a medieval duchy, various kingdoms, two independent republics, and socialist East Germany. Today, Saxony is a free state of the Federal Republic of Germany, and its external culinary influences are diverse. Imperial cities like Dresden and Leipzig have given Saxon cuisine rich, decadent dishes, while the state’s rural culture has contributed humble and hearty recipes with an emphasis on potatoes and cabbage. It is this dual character of haute and humble that defines this regional cooking style.

Saxons have a definite sweet tooth with numerous signature pastries and baked goods. Most importantly, the German institution of Kaffee und Kuchen (a mid-afternoon snack of coffee and cake) is said to have come from Saxony, where some of the first grand coffeehouses in Germany were built. Saxon cuisine also makes extensive use of freshwater fish like carp and trout as its neighbors to the east do.

Stollen. Baked during Christmas time since the 15th century, this hearty loaf is filled with nuts and dried fruits, then dusted with a coating of powdered sugar. The recipe arose due to a religious edict in Dresden prohibiting the use of butter during Advent—Stollen uses only flour, oil, and yeast, adding flavor with dried fruit and nuts instead.

Leipziger Allerlei. An Allerlei is a little bit of everything—peas, carrots, asparagus, mushrooms, and sometimes local freshwater crayfish. This mixed vegetable dish comes from the city of Leipzig, where according to legend, the humble recipe was served at local taverns after the Napoleonic wars to encourage unwanted beggars and tax collectors to move on to other cities in search of richer dishes.

Soljanka. This sour, spicy Russian-style soup has a base of meat or fish complemented by pickled cucumbers and mushrooms and topped off with sour cream and dill. This soup became popular in East Germany during the Communist period, due in part to local restaurants offering the soup to hungry Soviet troops stationed in the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

Hesse

The centrally located federal state of Hesse straddles the cuisines of northern and southern Germany, taking influences from both, but ultimately Hessian cuisine is unique in and of itself. As one of the main wine-growing regions in Germany, sour and fermented flavors dominate the Hessian palate. Hesse is also one of the largest apple-producing regions in Germany, and apples are featured heavily in local cuisine, whether in the form of apple wine or in desserts. Today, this region is one of the most international areas of Germany, centered around the world city of Frankfurt, and while Hessians increasingly consume foods from all over the world, traditional dishes remain at the core.

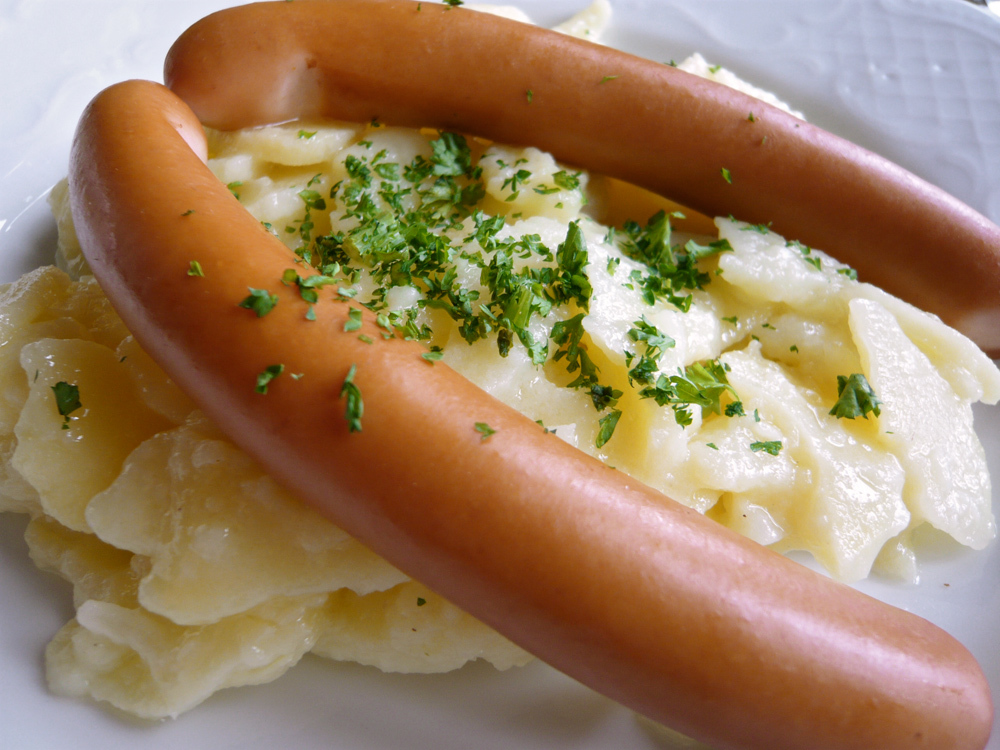

Frankfurter Würstchen. The original Frankfurter sausage, perhaps the closest relative to the American hot dog, is a thin parboiled pork sausage. They are slow-cooked in hot water for about 8 minutes to prevent the skin from bursting. Frankfurters are typically served with potato salad or on bread rolls with mustard and horseradish.

Frankfurter Grüne Soße. This green sauce is a specialty of Hessian cuisine, with the cities of Frankfurt and Kassel both laying claim to the recipe. The base of the sauce consists of pureed egg mixed with sour cream, to which seven green herbs are added (parsley, chives, chervil, borage, sorrel, garden cress, and salad burnet). The sauce is typically served with hard-boiled eggs and potatoes. It is said to have been Goethe’s favorite condiment; the writer was born in Frankfurt.

Handkäse mit Musik. Handkäse (hand cheese) is a strong sour-milk cheese that takes its name from the traditional hand preparation method. The dressing served with this pungent cheese contains raw onions, vinegar, and caraway seeds, and is called “with music” in reference to the flatulence the ingredients in this dish can cause.

Apfelwein. Apple wine is the official beverage of Hesse, and the city of Frankfurt has numerous bars specializing in apple wine. Frankfurter apple wine is particularly tart and sour due to the use of berries from the service tree during the brewing process, increasing the astringency of the beverage.

North Rhine-Westphalia

The most populous state in Germany, North Rhine-Westphalia is the nation’s industrial heart. Perhaps owing to its long industrial history, people from North Rhine-Westphalia have the reputation for being down to earth, practical, and uncomplicated—characteristics that are reflected in the local cuisine as well. Potatoes are both a main course and side dish in North Rhine-Westphalian cuisine, which is noted for its unassuming, substantial ingredients, thick stews, and predilection for meat and sausage. Kölsch beer from Cologne and Alt beer from Düsseldorf are popular both in the region and throughout Germany.

Pickert. A cross between a potato pancake and a dumpling, a Pickert is a large, flat, starchy concoction of grated potato with flour, milk, and eggs. The hearty peasant fare is served with savory sides, such as liver sausage, or as a dessert, with jam or powdered sugar.

Himmel und Erde. “Heaven and Earth” is a popular local Westphalian dish of blood sausage, fried onions, and mashed potatoes with apple sauce. The name references the main ingredients—the apples from the sky and the potatoes from the ground.

Pfefferpotthast. For this rustic stew, beef is fried in pork lard with onions and simmered for hours in a peppery tomato broth until tender. Bay leaf, cloves, and capers add an earthy note to the piquant stew. Naturally, Pfefferpotthast is served with a side of potatoes.

Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony is a large federal state in northeast Germany bordering the North Sea and the Netherlands. Agriculture and farming are important to the local economy, including fish and meat production as well as wheat, kale, potatoes, asparagus, lettuce, and carrots. The cuisine embodies the dual land and sea character of the region with an emphasis on fresh seafood and fish as well as pork, beef, poultry, and hearty vegetables. Areas of Lower Saxony like Friesland and East Frisia have some of the highest per capita tea consumption rates in the world. Here, tea is typically served with rock candy and heavy cream.

Grünkohl mit pinkel. Lower Saxony’s most iconic dish is a hearty plate of kale, along with smoked Pinkel sausages and bacon, as well as boiled potatoes. This is typically eaten in the winter months as kale is harvested only after the arrival of the first frost, which brings out its natural sweetness.

Buckwheat gateau. Buckwheat is a hearty grain that grows well in the cool, windswept northern climate. This layer cake is made of buckwheat flour with a layer of lingonberry jam, and it's topped with powdered sugar.

Smoked eel. Lower Saxony has not only a long coastline but also many large freshwater lakes, making saltwater and freshwater eel a local delicacy. It is typically smoked and served on bread.

Berlin

Berlin is both the capital city of Germany and one of the 16 federal states. The city’s cuisine showcases its traditional roots and increasingly international flair. As the largest city in Germany, Berlin is a multicultural metropolis, and the local food scene has evolved significantly since the fall of the Wall. Today, virtually any cuisine from anywhere in the world can be found in Berlin, but local favorites still play an important role.

Currywurst. The quintessential German fast food, Currywurst is a steamed and grilled pork or beef sausage, served with tomato ketchup liberally seasoned with curry powder. The dish got its start in Berlin in 1949 when local kiosk owner Herta Heuwer began selling the dish to hungry construction workers rebuilding the city. She flavored the sausage with piquant curry powder introduced to Berlin by British occupation troops.

Berliner. This fried yeast-dough donut, dusted with sugar and filled with fruit jelly, is an iconic Berlin pastry. In his famous speech, President John F. Kennedy proclaimed “Ich bin ein Berliner” (I am a Berliner), which actually means “I am a Berliner donut” since the article is left out when saying where one is from in German.

Döner Kebap. Berlin is the epicenter of Turkish life in Germany. In terms of population, Berlin is the second largest “Turkish” city after Istanbul. Essentially a sandwich of rotisserie meat with vegetables and a spiced yogurt sauce, this Turkish-style kebab is similar to Greek gyros or Arab shawarma. Germany’s first döner kebap was served in 1969 in Berlin, and today, it is one of the most popular take-out foods in Germany.

Königsberger Klopse. This recipe, which dates back to the regal days of Prussia, is a specialty of meatballs served in a white cream sauce flavored with capers.

Article written for World Trade Press by Carly K. Ottenbreit.

Copyright © 1993—2025 World Trade Press. All rights reserved.

Germany

Germany